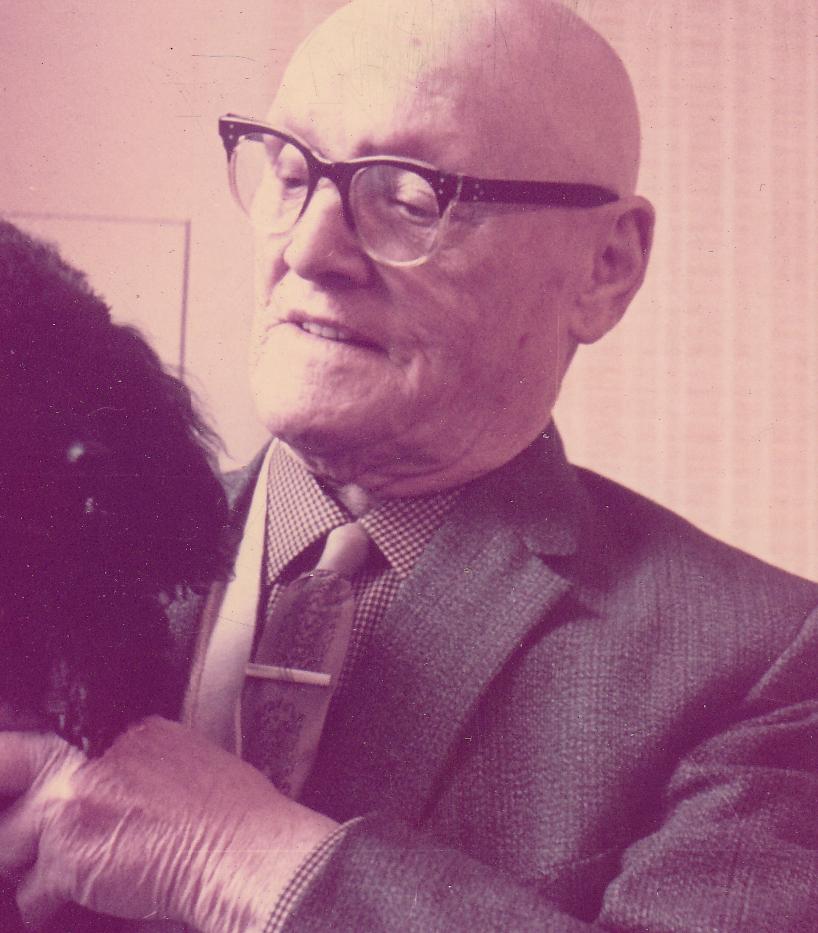

The lovely couple you see above are my mother’s Uncle Alec and Aunty Polly (aka Alexander and Elizabeth Nutter (nee Richards). When I was born, I was strangely shorn of grandparents; the only remaining one was my Gran Lightfoot, who lived over three hundred miles away in Cornwall (effectively, I only visited her about seven or eight times). Auntie Polly was my late grandmother’s sister, and I know my Mum saw her as a replacement mother. I loved the visits to their home…except for one aspect.

Writing this poem made me recall that I was an unusual over-cautious child; fearful of tragedy and death at an early age; unwilling to take risks that other children would not think twice about. It takes a person a long time to really understand themselves and I recognise traits in the neurodivergent children that I know now that were so obviously a part of my own childhood.

BURLINGTON STREET

As a small child I’d often be taken to visit

My mother’s Aunty Polly and Uncle Alec;

The walk, passed through sylvan woods

That left no sense of their existence

Between the edges of two hard-working mill towns.

A final drop down over the Hard Platts

To the railway line and main road

That connected the both of them.

Across the road was Burlington Street.

My trepidation on arriving at the top

Of a cobbled street that plunged 45 degrees,

Leading directly down to a spiked fence

At the bottom, beyond which was the canal,

Was palpable and despite my young years;

I could imagine the possibility of losing control

In some way and being swept down that wormhole

To a death of either impalement or drowning.

Arriving at the front door of No 14,

I would force myself to pull my gaze away

From the impending possibility of death and

With one leg outstretched and the other flexed

I would line-myself up with the deckchair-stripes

On the heavy canvas that protected the door

From the ravages of the sun.

Dad would ease the canvas to one side

And knock on the faux-wood painted door.

Silence…then a stentorian voice would call out,

“There’s nobody in!” A pursuant silence

And there it was, that moment for a child…

Uncertainty, pondered over for mere seconds,

Then realisation, like the fifth of Five Boys.

That everything was going to be fine.

Uncle Alec, a presence, would answer the door

And I would hop in, knowing now I was safe,

At least until it was time for us to leave.

He would beckon us in with his booming voice

Acquired from having to supervise and maintain

Forty screaming looms and the women that ran them.

Totally bald, a victim of alopecia,

His functional, black-framed glasses,

Doubled as eyebrows over his kind eyes.

Built as sturdy as a Northrop loom;

The bulwark defending the loveliness within…

Auntie Polly, as sweet as the saccharin dust

That lingered inside the tiny empty tins

That I would play with; wetting my finger

And tasting only delight there.

Both in their seventies, the trappings of children

Were long gone from their house

And I would be given the button box to play with

Or the woollen footballs she would make for me.

When the diabetes took her away,

Uncle Alec moved to a small cottage

A few streets away on the main road,

Beneath the towering spire of St Mary’s church

And far away from the perils of Burlington Street.

I wondered if he, like me, was glad to be away from it.

We would still visit him and Dinky, his toy poodle,

“A companion…someone to talk to” …right up to

The point I introduced him to my future bride.

I was happy that they seemed to like each other.

Alec lived to be ninety-three despite

A lifetime spent in the cotton mills of Nelson.

But those snow globes illuminated by northern lights,

Were bound to have a deleterious effect

On the lungs of a Lancashire tackler.

He’d struggle to bring up a great wad of phlegm

And spit it onto the coals of the open fire

Where we would sit and watch it dance and sizzle

For a second or two… until it was gone.

©graylightfoot